I remember James Island. At least, I remember a version of it.

When I first moved into the Chesapeake Bay area in the mid-90s, there was an island nearby – actually two, at the time – in the mouth of the Little Choptank River on the eastern side of the Bay. I used to fly over it often, and since it was relatively remote and uninhabited, I would often fly fairly close to it.

The southern island was covered with pine trees. It was maybe 10-15 acres in size, and the trees on the western side were always falling into the Bay as the waves encroached and undercut the beach on which they stood. The northern island, maybe 200 feet away, was bigger. Maybe 40 acres, and it was comprised of two pine-covered uplands with a sandy isthmus connecting the two.

This was James Island. It was the closest example of many uninhabited, tiny pieces of nature in the Chesapeake. Most of the similar islands are farther south, spread out in a chain that extends from Taylor’s Island down to the populated but isolated communities on Smith Island, MD and Tangier Island, VA. Residents of those islands often speak of the fight to save their community from forces both natural and societal, but watching James Island, week after week, really put that into perspective for me.

Storms, Erosion and Rising Water

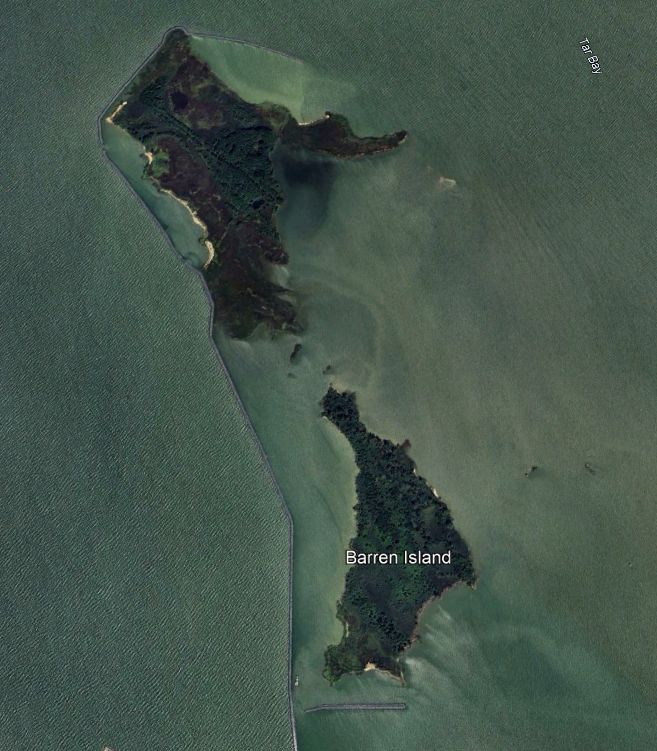

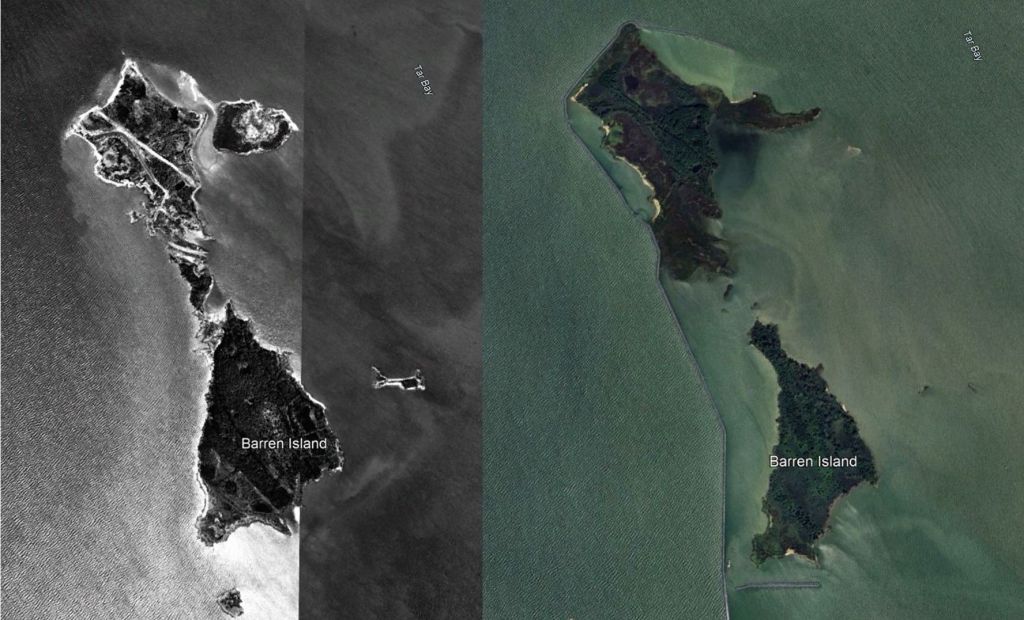

One day, not long after a hurricane passed through the area, I noticed the sandy bridge on the northern half of James Island was gone. Two islands were now three. In a similar event, I remember the day in 2003 when we realized that Hurricane Isabel had split Barren Island in two. Barren was more substantial than James, and a little farther south. It was no longer inhabited, but it had been at one time, and there was clear evidence of human activity – a few levees marking farm fields, some rudimentary roads, and a few deteriorating structures. Just like that, Barren was now “the Barrens”.

Closer to home, Isabel demonstrated to me how easily this happens. The same storm threw waves over a breakwater on the Bay shore close to where I live and flooded a pine forest. Saltwater got into the root systems of those trees and poisoned the ground. The trees died, and most collapsed a few years later. Had the breakwater not been there, it’s easy to imagine those acres disappearing quickly as the roots let go of the forest floor and let it all become loose sand again. Every wave would have claimed it, and returned it to the Bay.

That’s how it seems to happen. It’s very gradual, and then it’s extremely sudden. Bit by bit, and then in catastrophic events, the land is reclaimed by the irresistible forces of the Bay, and the steady rise of the water level.

The Bay is rising at a rate almost twice that of the global average. The average mean tide in this area is 4mm higher every year – an almost imperceptible amount that adds up to about 16 inches per century, a foot and a third. Extreme high tides are more common as well – though since we tend to define “extreme” in human terms by the degree to which the water covers boardwalks, floods marinas and shoreline roads and structures, it’s not really that high tide events are more common or unusually severe. It’s just a simple truth that the average tides really are higher than they used to be. The trend shows no signs of stopping.

It’s enough that 30 years after I first saw it, what I remember as James Island is completely, utterly gone. Occasionally, during an extremely low tide, a few spots of sand are visible where James once was. Viewed from above, the water color belies the fact that the water is shallower here, extending north from Taylor’s Island in a submerged sandbar that still poses a hazard to navigation, but visible only on charts.

The same thing happened a few miles to the north, in the mouth of the Choptank River, where the Sharps Island Lighthouse was built on a sandbar about a quarter mile north of its namesake island. The current light is the third one to mark the island, and it was built in 1882. Charts from 1904 show a sizable, inhabited island that even at the time was a mere shadow of its former, 700 acre self. By 1942, the island was only 17 acres, and a few years later, it was gone. Now, the lighthouse stands alone, with no land around it for miles. Its sad state is emphasized by the 15 degree tilt of the structure, the result of being dislodged and knocked over by ice in 1977. Ice… another thing we don’t see much in the Chesapeake these days.

History: Ice Age Through 17th Century

Thousands of years ago, during the last Ice Age, the weight of the massive glaciers that covered much of Pennsylvania and New York elevated the land around the Chesapeake. The land behaved like a massive teeter-totter, a lever that lifted the crust of Maryland and eastern Virginia as the ice pressed down in the north. Now that the glaciers are gone, the land in the north is rebounding, and the area around the Bay is settling back down. This is a process called “subsidence”, and it adds to the global sea level rise caused by melting ice sheets and climate change to create a more rapid change in the Chesapeake. The farther south you go, the worse the effect of subsidence is – it’s more noticeable in Hampton Roads than in Havre de Grace. This is the primary reason why sea level change is so fast here – the water is coming up AND the land is sinking down.

The Bay is a significantly different place than it was when Captain John Smith explored it in the 1600s. It’s estimated, and in some cases evidenced by the charts Smith and his crew made, that hundreds of islands have vanished since that time, and mainland shorelines have significantly changed. In fact, most of these islands – even James – were inhabited and farmed for hundreds of years. James used to be an estimated 1,350 acres in the 17th century, and in the time since then it was home to settlements, farms, oyster houses, and later a gun and hunt club. Post-glacial subsidence has contributed to erosion that has been ongoing since the island was originally charted – it’s been shrinking since Europeans first laid eyes on it, and likely long before that. The rate of loss of land in the Chesapeake has increased since 1850, and shows no signs of stopping.

Prevention and Restoration

So what are we to do? Anything?

We can’t stop the subsidence of land in the Bay, but we could certainly do all the things we know need to be done to slow and hopefully reverse climate change. This situation is a little like walking on ice – you know that sense when your feet first start to move out from under you, and you scramble and shift your weight desperately to maintain balance, but at some point you realize you’ve already lost the battle and start maneuvering your arms to make the inevitable fall less painful? That’s how I feel about the climate these days. We’re already falling, but everything we can do to soften the landing is absolutely worth it. If we’re lucky, we’ll be able to get back up.

Some of the islands (like Tangier, Smith, and even Barren) have been reinforced and protected by modern engineering. Huge barriers of stone riprap have been erected to absorb the relentless wave energy from the Bay, and to redirect the processes of erosion from more sensitive areas. The farms on Tangier and Smith are long gone, defeated by saltwater intrusion in those cases where the Bay hasn’t already utterly flooded the land. The communities there are now dominated by fishing, including harvesting of crabs and oysters. Maybe the stone barriers will delay the disappearance of these places for… long enough? Long enough for what, exactly? It’s hard to believe these islands won’t eventually disappear, too. Sixteen inches of sea level rise (per hundred years) is a lot in a place that is already half underwater at high tide, and where many structures are already on stilts and accessible only by boat.

North of James, and north of what used to be Sharps, another tactic is in play. During the same time I’ve watched James disappear, Poplar Island has been growing. The restoration of Poplar Island has been an ongoing effort by the state of Maryland and the Army Corps of Engineers to recreate marsh and upland wildlife habitat on a spot where Poplar once stood naturally. It looks like – and I’m being generous here – a landfill. The 24-hour high intensity lights and noise from earth moving equipment has diminished over the years, but you’d never mistake the reconstructed island for anything natural. It’s surrounded by a 20-foot-high dike of stone, and contains enormous amounts of sand, mud and other dredge removed from Baltimore Harbor and the various shipping channels in the Chesapeake year after year.

By 2030, Poplar Island will be “complete”, or maybe “full” is the appropriate word. At that point, it will be returned to wildlife again, and I have no doubt it will serve as a useful stopover for migrating waterfowl and other creatures. Clearly manmade – but likely “natural”, eventually, beyond the barrier wall.

Starting this year, James Island will get the same treatment. A new construction project will result in the recreation of James Island on the spot it once stood. Dredge material will be piled up inside a rock wall 9 miles long and enclosing over 2,000 acres – much larger than I’ve ever seen it, and bigger even than Capt. Smith likely saw – and it will continue to accumulate material until roughly 2067.

This effort is clearly not about “restoring” an island, though it has been pitched that way. James is gone, just as Sharps is gone, and just as Barren and countless others will be. Poplar is also gone, replaced by a landfill. The new island will be called “James Island”, but it is really just a convenient, shallow spot where it is easy (in the grand scheme of things) to pile up the shifting sand and mud from places we don’t want it – in shipping channels – and to contain it in a place where it hopefully won’t go anywhere. Putting that on the sandbar that used to be called James Island doesn’t recreate the island – but if we want the Port of Baltimore to keep operating (and of course, we do), we’ve got to put that material somewhere. James makes sense – and to some degree the wildlife that call the area home will ultimately appreciate the land, the marsh, and the lack of humans, even if the whole thing is a human construct.

To give Maryland and the Army Corps of Engineers some credit here, this won’t be a cheap project or an easy effort. James is a long way from Baltimore, and it’s apparent that some effort has been made to use the natural location of the island to minimize changes to existing currents and sediment deposition, as opposed to dumping all the mud somewhere that would probably be cheaper but more disruptive. Yes, it’s a shallow spot, but it also involves going the extra mile to utilize this location in the interest of working with natural forces.

Regardless of how you may feel about this, all of it – disappearing islands, new islands, the digging we have to do to keep channels open – is a fight to create consistency in a world that is changing, and will continue to change. We can delay the effects of climate change and subsidence, and we can try and regenerate what was lost, but we can’t deny that the change is occurring. Give it enough time and it is obvious, even within our short lifetimes.

Get Out There www.flying-squirrel.org

Other Reading:

- "The Chesapeake Bay: Geologic Product of Rising Sea Level", United States Geologic Survey (USGS), 1998

- "A Photographic Farewell to James Island", Jeremy Cox, Bay Journal, Oct. 2022

- "Chesapeake Bay Island Restoration to Benefit Wildlife, Port", Patch.com, Aug. 2019

- "James Island Losing Ground In The Chesapeake", Dan Rodricks, Baltimore Sun, June 2019

- "Feds, State Close In On Building New Island In Bay", Jeremy Cox, Bay Journal, Jan. 2025