Armadillos are… unique. The ones that live in the United States, the nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) are smallish mammals, around 30 inches long (about the size of a raccoon, groundhog, or skunk) but they are covered with leathery armored overlapping plates that wrap from left to right across their bodies. From underneath this “shell” emerge a long, thin naked tail similar to that of an opossum, and a pointed face with beady eyes and large (proportionally) pointed ears. Underneath, four legs are equipped with serious digging claws. The result is a strangely cute, snuffling animal that hunts mostly by scent (their eyesight is not great), and that can roll up into a leathery protective ball like the mammal version of a pillbug or isopod when threatened.

My favorite armadillo encounters have all been in Florida, but the most notable (and my first) was as a Virginia Boy Scout on a trip to the Keys back in the ’80s. Somewhere near Tampa, our Troop was visiting another group for some cultural exchange, and (not knowing any better) we left a half of a watermelon unattended. When we got back to camp, we found that an armadillo had climbed up onto the picnic table, rolled the watermelon onto its side, and just eaten its way through the juicy melon into the hemispherical shell, which it did an admirable job of cleaning. We saw a little alien (to us) grey animal – at least the back half plus a tail – hanging out of a watermelon, too distracted by its treasure to bother turning around and trying to escape our curiosity.

Armadillos are native to the Americas (today’s living species all originated in South America) and are in the same family as anteaters and sloths. The word “armadillo”, in Spanish, literally means “little armored one”. The Aztecs called them āyōtōchtli, which is a Nahuatl word meaning “turtle-rabbit”, which is also an apt description.

The reason I’m writing about them this week, though, is that they’re on the move (and because I was on a road trip this weekend and saw one in Alabama, the first I’d seen in years). Growing up, armadillos were associated with Florida and Texas, and apparently they weren’t even spotted north of the Rio Grande before about 1850 – but now, they’ve been spotted as far north as North Carolina and Illinois, and their range seems to be expanding up to 10 times faster than the typical small mammal. It is expected that they may become “local” backyard animals here at my home in the mid-Atlantic in as little as twenty years. It’s frankly crazy to me that armadillos may be common animals in my home range, just because, well, they’ve never been here in my lifetime. But, I guess the same is true of coyotes over the same period in time, so I guess I do have the capacity to adapt… just like they do!

Prior to 1850, nine-banded armadillos seemed to be stuck south of the Rio Grande. They’re decent swimmers, but the river was just too much. On the north side of the river, the land was mostly prairie, managed by native people through periodic burning. Armadillos don’t really like open grassland, so there wasn’t much motivation for them to venture there anyway. On top of all this, armadillos do have predators, and in the early 19th century they would have been hunted by wolves, cougars, jaguars, and people.

Beginning in the late 1800s, though, things changed. People were crossing the river more frequently (and likely bringing armadillos with them, either intentionally or accidentally). The suppression of native culture put an end to the fires, which let mesquite spread through the grasslands – a more inviting habitat for the armadillos. Increased human presence and killing of large predators also lessened that danger. There were also some accidental releases – the Florida armadillo population began when armadillos escaped from a zoo in 1924, and then a circus in 1936.

But external circumstances aren’t the only things armadillos have going for them. They have some built-in behavioral and biological advantages that make them adaptable and prone to expansion as well. Armadillos have a high reproductive rate. They routinely give birth to identical quadruplets, and they can delay implantation of fertilized eggs for up to 14 months until conditions (food, shelter, weather) are more favorable to raising young. They also live a long time, up to 20 years, so a healthy female can have a lot of young over her lifetime. In combination, these features allow a relatively small number of armadillos to establish a large breeding population in a relatively short time.

So, what’s stopping them? As adaptable as they are, armadillos do have specific preferences and vulnerabilities. They have low body fat (their armor is for protection, not warmth), and thus a low tolerance for cold. As mostly nocturnal hunters, armadillos don’t like it when the nights get too chilly. As a benchmark, scientists have estimated that an average low temperature of 28 deg F (-2 deg C) in January is a reasonable limit. In addition, armadillos need at least 15 inches of annual rainfall, so true desert life is not for them. Preferentially, they seem to thrive in hardwood forests, and removal of those ecosystems seem to limit their spread.

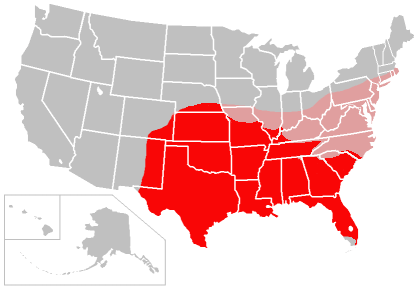

Looking at these limitations, wildlife conservationists have made some predictions about how far these animals may continue to spread. The resulting map (shown here) indicates that we may see regular armadillo habitation from southern Nebraska and south-eastern Colorado all the way to southern New England. They’ve already been established in North Carolina, particularly in the western counties (there have been reported sightings across most of the state, but verified, established populations only in 6 counties near the Smokies). Sightings have also started to increase in western Kentucky and southern Illinois.

Should we be worried about them? Not really. Armadillos can do some damage through digging and burrowing. The impact of this isn’t necessarily clear, and may differ depending on specific location. It’s possible that they may harm certain plant species, or harm ground-nesting bird populations, but that remains to be seen. They (oddly enough) can carry leprosy at very low (less than 10%) infection levels, but this isn’t a concern unless you’re directly handling them.

It is clear that these little adaptable animals are taking advantage of good habitat and warming winters to push farther and farther north. So, even if you’ve always only heard of armadillos as a Texas animal, there may soon be some denning up in your backyard. As long as they’re not doing any damage, enjoy them – they really are adorable, in a strange sort of way.

Get Out There

My first experience with armadillos was as roadkill in Mississippi. We didn’t see our first live one – foraging along the roadside – until years later in Texas. As the only animal other than us capable of contracting leprosy, they’ve played a role in research of this disease. And they are kind of cute. But, these days, I’d be more concerned about why their range might be increasing (climate change) then about the critters themselves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, some of their spread is certainly related to climate-change – those areas above 28 deg F are farther north than they used to be. But even without that, it seems these guys, once across the Rio Grande, have never fully established themselves in all the places they COULD, and they seem to be trying really hard to do that.

LikeLike