Back in October, 2018, the BepiColombo mission launched. It intrigued me then, and I made a note to learn more and write about it at the time. What piqued my interest most was the journey BepiColombo would have to take, a journey of over seven years to reach a planet that’s only an average 48 million miles away. Mars, by contrast, is 38 million miles away at its closest approach, and it only takes seven to eight months to get there. Interesting…

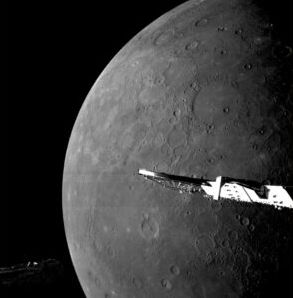

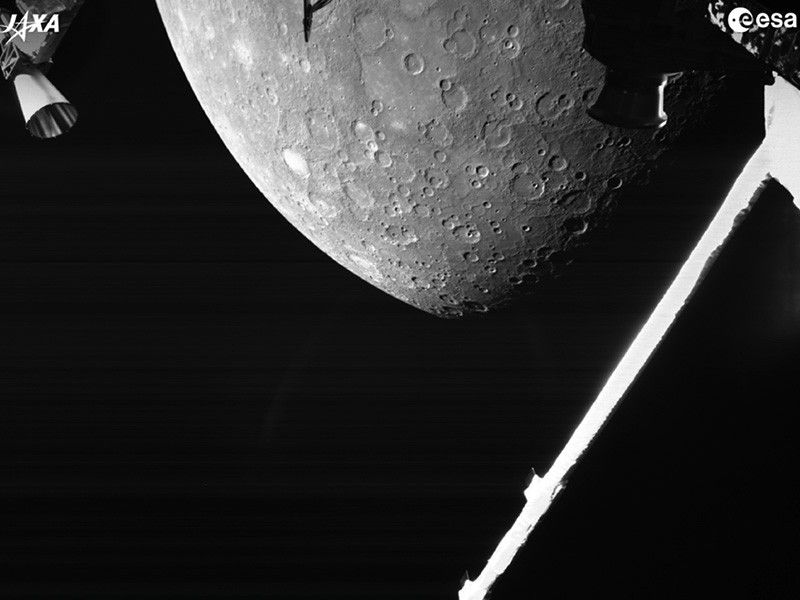

Well, one thing led to another and my investigation took a hiatus. But here again a couple weeks ago (January 8), BepiColombo made the news when it made its most recent flyby of Mercury – the last, in fact, before the orbiters will settle into orbit around the tiny planet in November 2026 (originally planned for December 2025). This triggered a memory, and so I dug back in.

BepiColombo is a joint project by the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), comprised of two separate orbiters have been sharing a very long, complex journey to the innermost planet. When they finally reach orbit, ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) will study the surface and interior, while JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) will establish a higher orbit focused on measuring Mercury’s magnetic field. We’ve been there before – Mariner 10 flew by Mercury in 1974 and 1975 and did it in only 147 days, but it didn’t stop. More recently, NASA’s MESSENGER started orbiting Mercury in 2011 to map the surface, and it took six and a half years to make the trip. So, clearly actually getting to orbit around Mercury takes a lot of time… but why?

Like most things involving space travel, it’s complicated. It seems intuitive that falling toward the Sun is fairly straightforward, but it’s actually easier to send a spacecraft to outer planets than it is to travel inward.

Leaving Earth, you may have noticed during a typical rocket launch, requires a lot of speed. Low Earth Orbit typically takes around 7.8 kilometers per second (km/s), or 17,000 miles per hour (mph), with respect to the Earth. With respect to the Sun, however, the Earth itself is orbiting at about 29.8 km/s (66,700 mph). In other words, we’ve spent a lot of energy to be orbiting the Sun along with the Earth. Now, a conundrum – we have to go even FASTER to get away from the home planet, but if we want to fall inward toward the Sun, we have to slow down.

Anything we launch into deep space has to reach a speed of around 11.2 km/s (25,000 mph) to escape the gravity well and truly get away from Earth. This is our planet’s escape velocity, so we have to be going at least this fast with respect to the Earth to go anywhere else. We can be clever about it though, since this is an Earth relative speed – if we fire thrusters at a point in the orbit when we’re moving around Earth in a direction opposite to Earth’s travel (typically, orbiting eastward, but on the daylight/sunward side of the planet), we can accelerate with respect to Earth and decrease our velocity around the Sun at the same time. In other words, we’ll accelerate away from Earth and fall into a solar orbit. But we will be falling quite a distance, and the pull of the Sun will be accelerating us until we pass around the Sun and head back out again. Without any adjustments, by the time we get to the orbit of Mercury, a mere 42 million miles from the Sun, well under half the average radius of Earth’s orbit, our spacecraft will be travelling INCREDIBLY fast, and trying to drop into orbit around a very small target, while doing so in the vicinity of the very large gravity well of the Sun itself.

Now, Mercury is fast too. In order to maintain its orbit, it has to travel an average of 47.9 km/s (107,200 mph). Meanwhile, its escape velocity (this speed relative to Mercury) is a very low 4.3 km/s (9,600 mph). So, we need to achieve an orbital speed matching that of Mercury, with a relative speed less than its escape velocity while moving in the right direction to drop into a stable orbit (all while looking over our shoulder at that massive Sun trying to pull us away).

So, the trick here is to an establish a solar orbit that matches the orbit of Mercury as closely as possible when at its orbital distance, crossing its orbit at an angle that is as shallow as possible, with speed as close to that of Mercury as possible, and to make that intersection at a point in space and time that Mercury also happens to occupy. However, our initial solar orbit extends all the way out to Earth, since that’s where we’re starting from.

The most energy effective way to do this is… gradually. And that has been BepiColombo’s experience. After launching in 2018 and establishing a solar orbit, BepiColombo made a pass by Earth in 2020 and used Earth’s gravity to slow down and lower the overall orbital altitude. Later in 2020, and again in 2021, BepiColombo performed flybys of Venus to further shape the orbit into something tighter (closer to the Sun) and more circular. Then, starting in 2021, the probe made 6 passes by Mercury itself, each time using the planet’s gravity to adjust the shape of the orbit. All told, BepiColombo will have made 18 orbits around the Sun before it finally starts orbiting Mercury.

At the same time, ESA and JAXA scientists have been able to use these passes to test and calibrate instrumentation and equipment. In April 2024, engineers realized that an electrical problem was preventing effective power distribution between the solar panel array and the rest of the systems, and limiting the amount of electric propulsion available. This effectively meant that the final approach to Mercury would have to hit an even narrower window of space and time, because it would not have sufficient power to overcome large errors. In order to compensate, BepiColombo’s trajectory was altered so that its fourth pass was closer to Mercury, reducing the amount of power needed to adjust for the fifth and six passes. Those final two passes would also make more significant changes to the overall trajectory – in effect leaning on Mercury more, realizing that we could then rely on thrusters less. As a result, BepiColombo’s arrival has been delayed by 11 months, but will be a more energy-efficient insertion with a planned orbital insertion now scheduled for November 2026.

This is a very rough, one-dimensional analogy, but pretend you have to throw a tennis ball to a friend standing on a balcony eight floors up. And he’s got a bucket to catch it in. It takes a LOT of energy to get the ball moving fast enough, but if you do it right, the ball will essentially stop right in front of him, and he can reach out and easily snag it in the bucket.

Now, imagine the opposite. Your friend has to toss you the same ball from the balcony to the ground, and you have a small Styrofoam coffee cup (representing Mercury’s smaller gravity well) to catch it. Worse, he can’t just hold it out and let go, he’s got to throw it UP a little first so it’s already moving when it goes by him on the way down. You’re going to have a much easier time if you let the ball bounce a few times, losing energy, getting lower and slower on each bounce, until you can finally snag it.

It’s a long, complicated journey, and I admire the skill and precision of the flight dynamics crews that have planned and executed the complicated dance with three planets (and the Sun of course) to make it successful. I’ll be looking forward to hearing that the two probes have separated and achieved their respective orbits in November, 2026.

Get Out There!

Further reading:

ESA's BepiColombo Mission Page

NASA's BepiColombo Mission Page

Understanding and describing orbital mechanics is not intuitive to most people. You did a good job explaining why the trip is so complicated and lengthy. Thanks for the details. Let’s hope the mission goes well with no problems.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, appreciate that. I’m impressed by the fact they already had a pretty significant problem and were able to work within the existing limitations to adjust, at a cost of only about a year. I agree, hoping everything works out well from here on out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another good space article, love the science.

On another but related subject, I’m interested in a startup, pre-IPO company:

Space X has become a wildly successful financial success, currently the largest privately held company. They charge millions to launch satellites and that business is growing, but launch costs are astronomical (pun intended) too. Reusable rockets help reduce costs but another problem is lapsed time between launches.

The startup enterprise has a different model: use Supersonic jets at Mach 2 to carry under-wing rockets that will propel payloads into orbit. They recognize satellite size limitations but the market for small satellites is also large and growing. According to marketing materials they’re already building a small fleet of jets (in Korea for some reason) and they plan launch operations from California and Texas.

Does this sound feasible, and what’s your reaction.

Larry

Get Outlook for iOShttps://aka.ms/o0ukef

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Larry.

My initial reaction: some aspects are very feasible, some are a stretch.

Air Launch To Orbit is well within current technology – Northrop Grumman is doing it with their Pegasus launch system (launching from a DC-10 at 44,000 ft) up to a payload of 1,000 lbs. Virgin Galactic was doing suborbital tourist flights from an air launch, companies like Stratolaunch do it with missiles… Heck, even though they weren’t designed to go to orbit this kind of thing has been done since the late 40’s – The X-1 launched off a B-29, the X-15 launched off a B-52… There’s advantages here, mostly in dealing with less drag for less time, which means less fuel needed, which significantly lowers overall weight, etc, etc. Given that the aircraft has to lift the whole launch system, we’re currently limited to smaller payloads, but you can do a lot with a one ton satellite.

The real challenging part of what you describe – I can’t figure out why you want want or need to get to Mach 2 to conduct a launch. First of all, Mach 2 at 50,000 feet is only ~1320mph. You still have to get to 17,000 for a Low Earth Orbit at the same altitude as ISS, for example. The difference between launching from a subsonic platform at 600 mph and getting to 1320 mph is a TINY fraction of the 17,000 you need… and that 720 mph or so is VERY expensive to achieve with an air-breathing vehicle. Supersonic flight is horribly inefficient in terms of fuel burn alone – the energy required to get the launch platform to Mach 2 likely exceeds the fuel/cost savings you’d see on the rocket by launching at that higher speed. I’m doubtful it would buy you a significantly larger payload (which remains the most significant advantage a surface-launched system has). On top of that, the actual launch and separation of an orbital vehicle from mothership is much more challenging at supersonic speeds.

Consider that Boom Supersonic just flew their demonstrator this week, and that’s the first commercial supersonic aircraft since the Concorde. It’s just hard (and expensive) to do, and in my opinion, not worth the extra cost over using an existing SUBSONIC jet platform at high altitude for this mission.

Ultimately you’ve got to ask yourself what this startup is doing (either technology or business model) that results in a significant efficiency increase over existing tried and true methods. A simpler/cheaper approach might very well compete with Northrop Grumman… but the launch platform you suggest sounds (to me) like a lot of cost and unnecessary headache to achieve a very small (perhaps non-existent) benefit.

Good luck to you.

LikeLike

Whew, that was a lot to digest. Thanks for the lesson!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, this is a tough one – but like I said, a lot of the reason I’m doing this is because it compels me to dive in to stuff I know generally, and learn it more specifically. I was really looking for a “map” that showed the various flybys and what that did to the orbits over time, but even the mission planners seemed to have trouble generating something simple enough for public consumption!

LikeLike

Thanks for the much needed explanation of why it is so difficult to reach Mercury and why it takes so long to do it.

Similar factors would all come into play at some time in the future when we send the first high velocity probes to the Alpha Centauri system. Attaining semi-relativistic speed is one thing – but how to plan in advance a deceleration sequence which would avoid the inevitable shoot-through experience?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good question! Hopefully by then we’ll have a lot more experience, and propulsion systems that will allow some very high-G accel/decel.

LikeLiked by 1 person