Earlier in the week, I referred to an effort to find the dwarf planet Ceres, while carefully sharing a photo of Orion to disguise the fact that “finding” Ceres meant little more than identifying one dot of many as a rocky planet, and not a star like the rest of them.

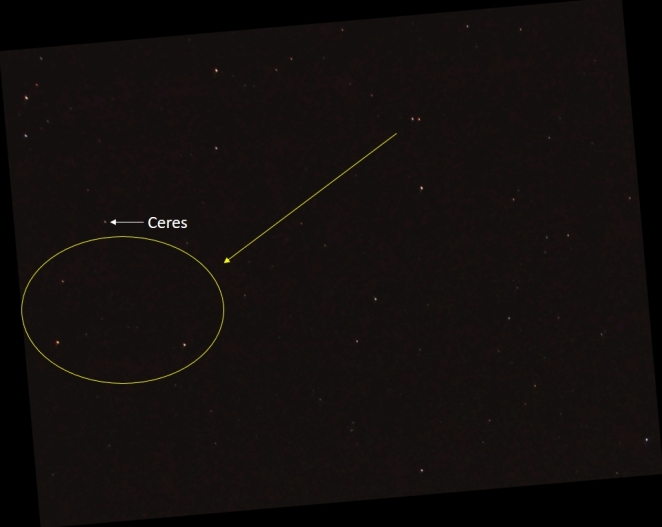

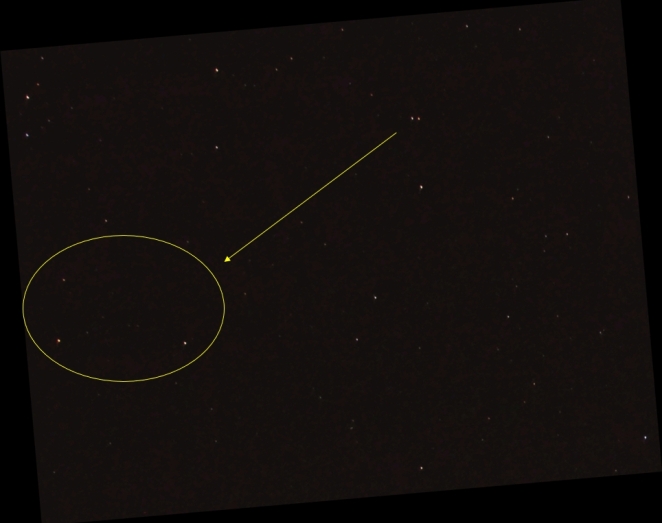

Ceres, Feb 6th, about 0015 UTC. Sitting right along the border of Cancer and Lynx. This image was made by stacking 22 photos, each of which was a 4 second exposure at 1600 ISO.

For me, “discovery” meant consulting star charts (in my case the digital chart, Stellarium – excellent program!), figuring out how to star-hop from the Sickle of Leo to the approximate location of Ceres, in dark, dark Cancer… then going out to find it. The combination of the relative emptiness of Cancer, and the light pollution washing out the few stars that would have normally been visible, meant that my star-hopping exercise was more of a guess… I literally had to point the camera in an approximate direction and take a four second picture – oh, THERE are the stars, ok move a little left, a little higher…

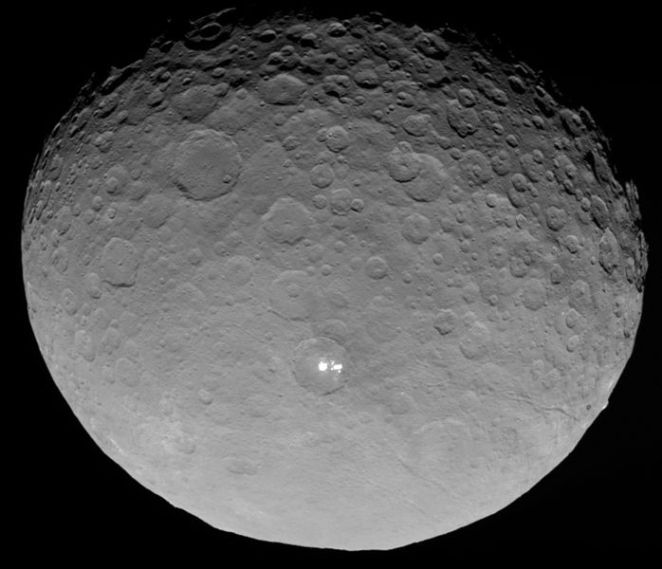

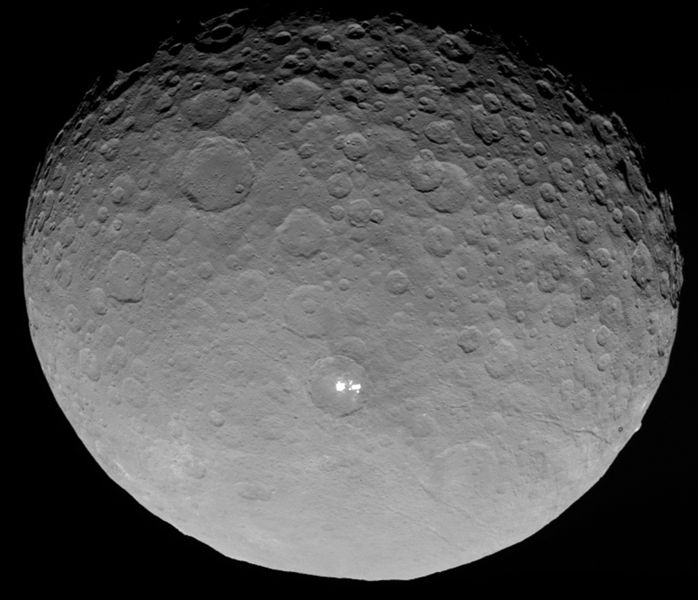

The above image, HIGHLY zoomed (by NASA).

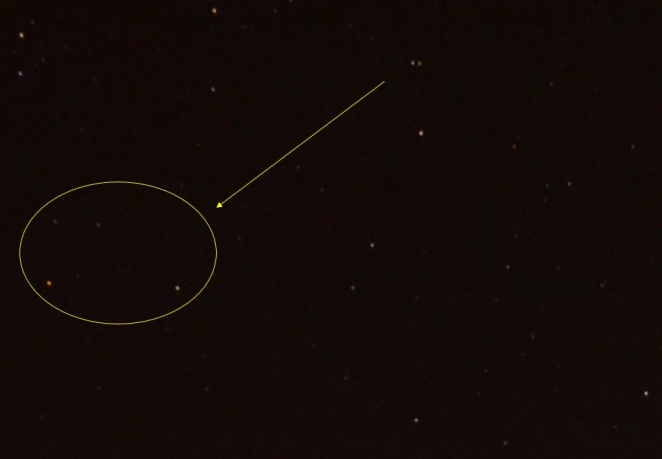

What made this endeavor interesting, and worth blogging about, is that last night I went and found it AGAIN. So I now have TWO dot-filled pictures, one taken on Feb 5, one on Feb 8. Each of these photos shows the same set of stars, in the same places – except one of them has changed positions. THAT is Ceres, orbiting the Sun and moving against the background. And it occurs to me, this is how a lot of these bodies (asteroids, comets, dwarf planets, etc) have been discovered in the first place.

Nowadays, computers do a lot of the grunt work, and most comets these days are discovered by computerized sky surveys. It’s easy for a computer and a little bit of Artificial Intelligence to do change detection, and notice something moving. Used to be, though, this was done manually, comparing two images and looking for a difference (like those games we used to play as a kid, “how many differences can you spot…”). OR, and I tried this as a teen, you can drive a telescope or camera to match sky motion due to rotation of the Earth and take a REALLY long (hours) exposure that tracks the stars, and notice one object (hopefully) leaving a streak across the frame due to movement other than by Earth’s rotation.

I realized that Ceres is brighter than I thought. These images are just straight JPEGs – you can really see the difference that stacking and enhancing makes! Anyway, using the distinct double star as a reference, you can navigate to this little trapezoid. One “star” here isn’t a star! (Taken Feb 6th, 0015 UTC – evening of Feb 5th in my local timezone…)

Before long-exposure photography, it was even harder – astronomers would sketch their observations while viewing through a telescope, and notice differences day over day. This is how Galileo famously discovered that Jupiter had moons orbiting it!

Again, in my case, I knew what I was looking for, and where. In those circumstances, it’s not hard to find something moving over the course of three days. But it’s easy to go cross-eyed looking at images like this – the patience required to actually discover comets this way is mind-boggling.

Three days later – Feb 9th, 0300 UTC. Same area (original photo rotated a bit to line up with earlier shots – this was taken later in the evening!) Notice the same double star, but the “trapezoid” is now a triangle! Ceres has moved out of the oval!

In any case, I found this a fun little exercise – not only FINDING Ceres, but proving that what I found was actually what I thought I found, and not just another star.

Get Out There!

Troy

http://www.flying-squirrel.org

Great work and good job on the perseverance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for inspiring me to look.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s really awesome, to be able to see that little dot move!

LikeLike